Supplementing the Record V

What was left out? That Zionism is Jewish supremacy—and that Madonna and her Hollywood team silenced anti-genocide voices in the wake of 10/7

Welcome to another edition of Paralipomena, the explicitly politico-intellectual adjunct to my flagship scroll The Book of Sean M. P.

Since my last written post I’ve embarked on a video series exclusively for paid subscribers featuring my unique perspective as a critical race theorist–cum-method actor with an unwavering focus on Palestine and the “indivisibility of justice,” as one of my mentors, Dr. Rabab Abdulhadi, always says.

Titled The Armenian Quarter or No Other Land and consisting of 15-minute commentaries on the news of the day, I’m producing this “Neo” daily show Mondays through Thursdays upon my return to Glendale from my day job teaching at a learning center for neurodivergent students in Pasadena.

I’ve also launched a “Buy Me a Coffee” for anyone who’d like to throw a Lincoln my way as a modest but very meaningful token of appreciation for the labor I donate to create all the “free” (that is, non-paywalled) content on this site.

And on the flip side of the coin, I’m eagerly awaiting an angel investor to come on board as the first founding member of my Pantheon, for which you’ll receive both my boundless gratitude as well as a one-of-a-kind personalized artifact from my archives.

Not already subscribed? You can take care of that business at any tier—free, monthly, or founding—by hitting the button below.

Now on with the show. <3

Express Yourself—Except on Palestine

Today—March 2nd, Gregorian year 2025—is not just the day of the Oscars but also the birthday of one of my greatest mentors of all time: the late Ingrid Sischy, a South African Jewish lesbian cultural force in the American and European entertainment, art, and fashion scenes for five decades until her death in 2015.

(Beat.)

As it happens, I was in South Africa when she died.

(Beat.)

Indeed, I was in Johannesburg, her place of birth, when she passed.

(Beat.)

But those two stories—the one about my tenure at Interview under Ingrid’s editorship and the one about my time in the motherland—belong to my manuscript in progress, Química Divina: A Testimony of Sexual—and Spiritual—Healing (which—by the way—you can advance by donating at that link or by subscribing to this scroll).

Instead, the story I want to tell now is about Ingrid’s friend Madonna, with whom I connected while on staff at the magazine, founded by Andy Warhol in 1969—and why I cut the cord with her because she’s a Zionist.

One of my jobs at Interview was to answer Ingrid’s phone when her own assistant wasn’t available to do so. (My main role as an editorial assistant was to support the film editor while executing general tasks such as factchecking and developing story ideas.)

Accordingly, I talked to a veritable pantheon of celebrities, including Elton John (who, as one of Ingrid’s BFFs, called all the time); Iman (on whom I famously hung up while still learning how to transfer calls); and the artist formerly known as the Queen of Pop, who didn’t phone regularly but who did do an interview with Ingrid while I was there—a conversation I recorded, on analog tape, through a device attached to a landline.

Connecting parties and capturing their chats was another responsibility of mine at Interview: calling publicists or other handlers, waiting till the “talent” got on, and then, in this case, putting Ingrid on the line.

Afterwards I’d transcribe the interview—at least, that is, as much as I was allowed to listen to, given the intimacy of Ingrid’s relationships with pals like Madonna. Sometimes portions of the tape were off the record, even to a behind-the-scenes minion like me, who otherwise absorbed all sorts of tea just by being in the wood-paneled office five floors above Prince and Broadway surrounded by tastemakers and Warhols.

It’s no secret that when I came to Hollywood in 2021 I wanted to be signed by Creative Artists Agency, whose CEO and co-chairman, Bryan Lourd, dated Carrie Fisher in the 1990s.

I indicated as much in my first post for this scroll two years ago, though you had to read between the lines to pick up on the tell.

It wasn’t just the Fisher connection—and the fact that her and Lourd’s daughter, Billie, went to Harvard-Westlake, a school to which I’m also linked through the students I’ve tutored who’ve attended it—that endeared me to CAA. It was also the agency’s reputation for being the most powerful in town—and its roster of clients, including five whom I adore: George Clooney, Nicole Kidman, Cate Blanchett, Jessica Chastain, and Lupita Nyong’o, the latter three represented by Hylda Queally, who intrigued me.

Indeed, as I anted up my lifelong “fake it till you make it” strategy in 2023 as my traction gained at the world-famous Hollywood Improv, I addressed the agency—and my fellow Irish people, George and Hylda—in a YouTube video. Though I had no specific intelligence that CAA had “hip-pocketed” me, I acted as if it had. That mindset kept me lifted.

Everything changed on Tuesday, February 18th, however, when I saw that CAA had signed Kamala Harris. It was bad enough that her boss, the former Zionist-in-chief Genocide Joe, had signed with the agency a fortnight earlier, but Kamala truly is a train wreck, having spent $1.5 billion in the 15 weeks of her disaster of a campaign.

Only in Hollywood—and Washington—could such a colossal waste of money with absolutely nothing to show for it be considered “talent.”

It was bad enough that her boss, the former Zionist-in-chief Genocide Joe, had signed with CAA a fortnight earlier, but Kamala truly is a train wreck, having spent $1.5 billion in the 15 weeks of her disaster of a campaign. (Beat.) Only in Hollywood—and Washington—could such a colossal waste of money with absolutely nothing to show for it be considered “talent.”

At that point I realized CAA had zero credibility. Too, I certainly didn’t want to be represented by an agency that also counted two criminals—under both international and domestic law—as their clients, to say nothing about the Holocaust in Gaza that they aided and abetted every step of the way—while publicly expressing the opposite.

That’s how plausible deniability works—and CAA is, of course, a master of the false flag, considering how stardom has traditionally been shaped in part through fabricated stories planted in the press.

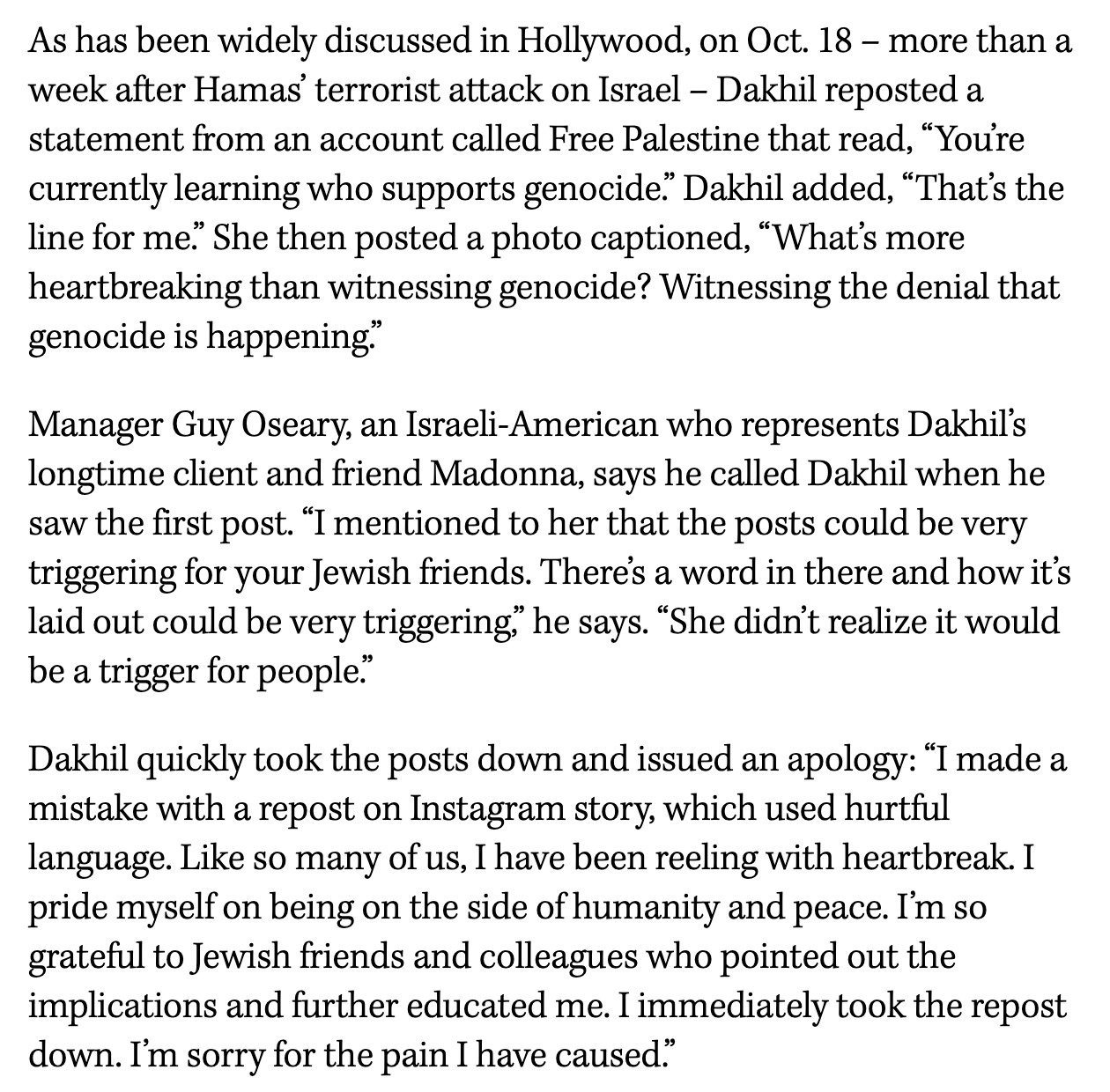

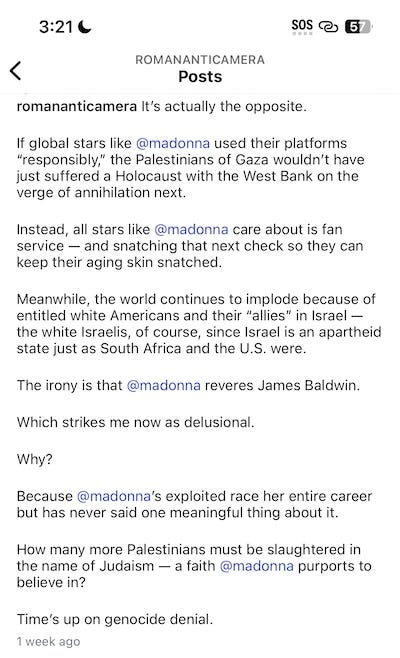

So when I revisited the “controversy” at the agency concerning genocide denial in the wake of 10/7, it was obvious what had happened: CAA overall; Madonna’s agent, Maha Dakhil—also the agent (and lately beard) for Tom “Scientology” Cruise—and her manager, Guy Oseary, had collaborated to stage the spectacle.

Why?

That’s an easy A: To make it seem like the agency wasn’t actually so Zionist because at least one of their heavy hitters was opposed to the genocide—when apparently there wasn’t any real dissent at all.

(To make matters even more peculiar, I went to a film screening at the agency’s headquarters with my then intimacy director in 2023 shortly before my Honda Insight was repossessed in exceedingly shady fashion.)

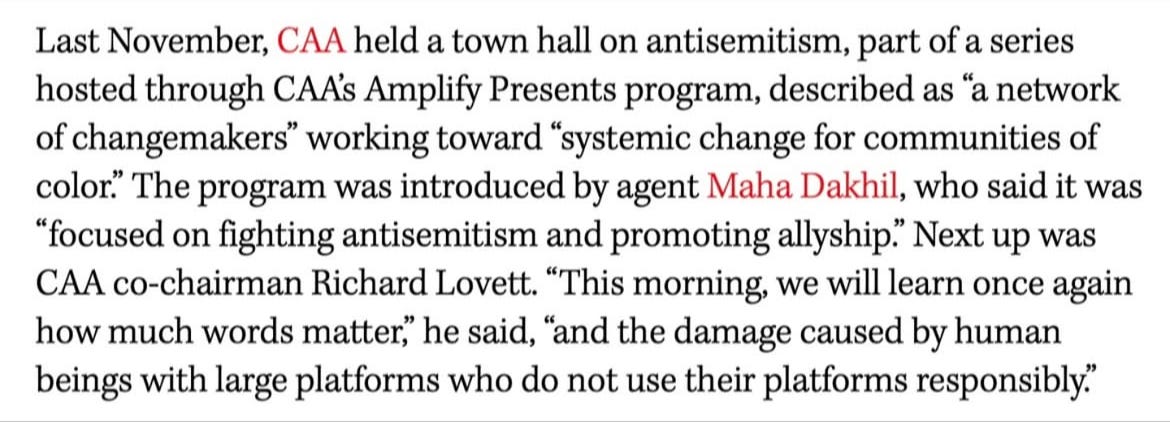

In fact, as I dug deeper, CAA—including Dakhil—had long only cared about Jewish people—the sine qua non of Jewish supremacy.

Indeed, as I state in the video at the top of this post—an excerpt from my new series The Armenian Quarter or No Other Land—that’s the agency’s understanding of “anti-Semitism”: the protection of Jewish people’s feelings at all costs.

CAA co-chairman Richard Lovett said “[t]his morning, we will learn once again how much words matter” as a preface to this anti-Semitism training, “and the damage caused by human beings with large platforms who do not use their platforms responsibly.”

[But] it’s completely the opposite: People with large platforms should be using them to save people’s lives.

Instead, what CAA instructed its “team” in terms of “anti-Semitism” and “allyship” is that nobody else’s experience matters. It’s the feelings of Jewish people that are paramount—and the lives of Palestinians, of Lebanese, of Syrians, do not matter.

Well that’s a problem, my friends. Because feelings aren’t human beings.

Too long, didn’t read: In sum, CAA put their huge thumb on the scale of genocide—and their middle finger in the face of Palestinians. In turn, that imprimatur licensed the widespread retaliation against so many Hollywood professionals who spoke publicly in support of Palestinian lives.

As for Madonna: Once upon a time, she was revered for being ahead of the curve. Now—in my book—she’s consigned to the dead stock of history for enabling both the Holocaust of Gaza and a climate of fear and reprisal.

I wondered as much when I saw her Noel tree this Chrismukkah past decorated in the binary colors of the Zionist entity—a colorway she emphasized in the sweater she wore posing in front of the plant.

No doubt the customary colors of red and green offended her false sense of anti-Semitism given their trumped-up association with Hamas.

But as George and Hylda surely know, Hamas is no different from Sinn Féin.

The Past is Present (From the Archives)

In another story I’m not going to tell here but in Química Divina, I was a longtime collaborator of the filmmaker Susan Youssef until we drifted apart in the late 2010s, culminating in a public falling-out in July 2020 over her theft of my labor on her film Marjoun and the Flying Headscarf.

That flick turned out to be a bomb: a seriously amateur foray that exploited both the U.S. civil rights movement and the horrors of Vietnam in service to a confused narrative about Islamophobia and the discourse of terrorism that was well past its sell-by date.

The film she released a decade earlier, though, Habibi Rasak Kharban, was dynamite.

The following is an interview I conducted with Youssef for the film’s publicity campaign. It reminds me of how beautiful Gaza is—no matter the current level of destruction—even though I’ve never been there.

That’s the power of film, if used responsibly—to counter propaganda and in so doing, to open viewers’ eyes to the only truth there is: that we’re all one people.

Based on the ancient Arabic romance Majnun Layla, Habibi tells the story of young Gazan lovers who are prevented from seeing each other by family, social tradition, and politics. The idea came to writer-director Susan Youssef while shooting Forbidden to Wander in 2002, a documentary that recounts her own romance with a theater director in Gaza. Nine years and numerous grants later, Habibi is set to seduce audiences worldwide. Youssef, a New Yorker, talked about the film by phone from Amsterdam, where she lives part of the year.

Why use Majnun Layla as your source material? You could’ve written the script from scratch.

Susan Youssef: There were two advantages. One, it gave me a structure that had been working for centuries. Two, I was completely enchanted by this idea of a poet who existed in the seventh century and whose name other writers for centuries have used to author their own love poetry. There’s an argument that the Majnun Layla poems aren’t by the original poet Qays ibn-al Mulawwah. I felt I could connect to that tradition of hiding behind his poetry.

But why choose a romance to tell a story about Gaza?

It was easy to make it a romance because my only link to the Gaza Strip was my own personal romance. And Gaza is an incredibly romantic place. The landscape is beautiful: there’s the beach, the tropical climate, fruit, palm trees. Then there’s the heroism of everyone that lives there. The landscape and the nature of the people living there and surviving seemed very romantic.

This is your second film set in Gaza. You’re Arab-American, but your father’s Lebanese and your mother’s Syrian. What draws you specifically to Gaza?

My first screenplays were almost identically linked to me: one was an Arab-American screenplay that I wrote as my thesis when I was an undergraduate, and one was set in Lebanon when I was a journalist in Beirut. I felt like I didn’t have the distance in order to give my characters the truth of their existence; I ended up telling the stories too much as myself, which does not make for very good narrative. I’m much more honest when I’m telling the story through another setting. Gaza, Palestine—it’s still the Levant, we’re still Semitic people. It’s almost what I know, but there’s a little bit more distance.

What was the process of making Habibi?

I fell in love in Gaza and the idea was just handed to me: I saw children acting out Majnun Layla in a gymnasium in Khan Younis. I found the poems at the New York Public Library. I went to Gaza in 2005 to shoot sample scenes. People were very willing to support the production. Across political positions they were really excited.

But you didn’t end up shooting the film in Gaza. Why?

In 2007, I wasn’t allowed back into Gaza. I waited in the West Bank not knowing what I was going to do. But Palestinians are very innovative people, and very hospitable and helpful. I met people from Gaza who were living in the West Bank—they suggested I try to fake Gaza there. But I delayed. Part of the reason it took me until 2009 to shoot was my belief that I’d get back into Gaza. When we filmed in the West Bank it was so painful, because there was a limitation on what we could film. How could I fake Gaza while shooting the West Bank landscape, with mountains in the distance? We couldn’t have wide shots—but that worked to create the suffocating feeling of Gaza. We had many other obstacles—I’m deeply grateful that I was able to find a way to tell the story.

What was the shoot itself like?

Because I’d been so adamant about shooting in Gaza for so long, I closed a lot of doors financially, in terms of being able to find producers, investment… The film had an extremely limited budget. That limited the number of people we could have on the crew. But I believe the camaraderie and intimate nature of the film set resulted in a film made out of love. I’m very superstitious: I believe the kind of energy that goes into a film goes a long way.

What’s your ultimate objective with Habibi?

I love the idea of bringing this poetry back to the mainstream. So that’s one goal, to share how amazing I find my heritage to be. And I believe in the hope of collective consciousness: that greater understanding of the situation in Gaza will somehow improve things there. This film is part of a continuum. I look to the U.S. civil rights and gay rights movements—much of their success has to do with collective consciousness coming through media, culture.

You were born and raised in New York City. How did you end up in Amsterdam?

Well, Mohammed in Gaza, with whom I had the relationship, advised me to go to the Netherlands—it was one of the countries he knew was funding theater in Gaza. It was ironic because in 2002, on the way to Gaza, I was detained at Schipol by Israeli security for interrogation. I applied for a Fulbright fellowship to the Netherlands and it worked out. I found a mentor my first week, Dr. Ihab Saloul, a scholar of comparative literature. He knew the Majnun Layla poetry, was from the Gaza Strip, but he also lived in the Netherlands and understood what was needed to culturally translate the story.

And what about Mohammed?

Things with Mohammed ended up not working out. Instead, in my last month of my Fulbright fellowship, I met my husband, Man Kit Lam, who edited the film with me. So I came to Holland out of love and I stayed in Holland out of love. [Laughs.] I have to thank this film and I have to thank the Gaza Strip because it’s completely defined my life through love.

True story, my friends: Gaza has also completely defined my life through love.

(Beat.)

How?

(Beat.)

Because the narrative of Majnun—of a poet who goes mad in search of his lost amor—is the exact script I enacted in my twin-flame journey with Arthur after we separated physically during the summer of 2020.

Ciao for now,

Sean M. P.

ICYMI⇓⇓

Supplementing the Record III

Greetings, core readers of The Book of Sean M. P., and welcome to all people making cameos. This is your host with the mostest, Sean M. P., inviting you to another Paralipomena, the explicitly politico-intellectual adjunct to the OG B.O.S.M.P.